‘I could almost feel another person’s feelings’

Notes on re-dramatising citizen engagement

Scripting, staging, and rehearsing policy processes can bring new insights into why citizen engagement processes break down and how they might be reimagined.

For our consortium meeting in Tartu, our team developed a workshop designed to highlight the power of re-dramatising citizen engagement processes. Our aim was to help our fellow team members to more deeply engage with the positions of the citizens, professionals, and policymakers involved in public participation. Our instinct was that by scripting, staging, and rehearsing citizen engagement processes, we would gain new insights into how citizen engagement processes break down. By drawing on the well-established technique of treating daily life as theatre, we wanted to re-stage a citizen engagement process, using CIDAPE research to construct the setting and characters, and the wider CIDAPE team as actors.

The work began with Christina's ethnographic research, in which she observes public participation meetings, shadows civil servants and citizens, and traces local developments around the policy issue. Her insight was that much as with characters in a play, each actor - citizens, policymakers, and professionals - brings their own backstory, holds different perceptions of what is at stake, and navigates a distinct emotional landscape. When reflecting on her ethnographic research, Christina remembered moments when she felt she could almost write characters based on all the stakeholders she had observed that year. Increasingly, she started to think of the ethnographic process as one of script writing. This reflected a longstanding interest at the Urban Futures Studio in treating social and political reality as theatre and analysing it as such. At the same time, within our CIDAPE Work Package 7, the idea of using rehearsals as a method kept resurfacing. Rehearsing a character's role, acting it out, we started to think, might allow us to gain a more sympathetic understanding of how it felt to be in their position. Further, it might help us to identify where they were getting stuck and where breakthroughs might be improvised.

The preparation

Three points were crucial. First, we knew we had to fill in the character's backstories with real research insights. For this, Christina turned to the wider CIDAPE team. She asked them to draw on their research into multiple different social actors and to imagine how those actors might perceive policy, feel, and act if invited into a public participation process. Some of us represented farmers, others manual workers, businesspeople, or opposition politicians.

Then we asked our colleagues to get into the 'backstory' of the stakeholders they engage with in their projects. To help colleagues get into character, they were encouraged to bring simple costumes, and we began with a guided meditation that invited all of us to take on the perspective and to empathise with our character's perspective.

Second, attending to individual feelings would not be sufficient. The beauty of the rehearsal approach is that it facilitates a better understanding of people's emotions, including a greater comprehension that emotional responses to climate change and climate policy do not arise in a vacuum. People's individual backstories interact with the people and situations by which they are confronted in daily life. This is what Christina's research told us was happening in public participation meetings. Citizens bring their frustrations - with life and politics as a whole as much as with a particular policy - and yearnings into the room as they try to understand what is being proposed and how it will impact on their life. Policymakers bring their own anxieties, habitualised ways of doings and aspirations as they try to fulfill their role of communicating policy. And all of these feelings collide, interact, and develop between four walls. From this perspective, simply becoming aware of the specific interests and roles of the actors involved is not enough. We also need to understand how they are positioned in relation to one another, and how the different backstories and relationships come to the surface in interactions.

Third context and, more specifically, the space itself matters a great deal. Christina's research into the sociology of emotions emphasises that context matters for how we behave and how we feel. Similarly, dramaturgy attributes a major role to the material context. Kenneth Burke contends that 'the scene, meaning the context or setting, shapes the act.' Erving Goffman, a key dramaturgical theorist, postulates that when entering face-to-face encounters, actors assess the context and arrive at a certain definition of the situation, which builds the fundament for the subsequent response. It is about both the sequence of events, and the spaces in which those events unfold. The way we act, feel, and relate to one another is shaped by situational and interactional conditions, with the personal, the social, and the physical being in constant dialogue. This led us to the idea of reproducing the settings in which participatory meetings take place. Christina turned to her fieldnotes, in which she had carefully recorded how audiences were arranged, what the stage looked like, which posters or banners were displayed. Drawing on all these details but translating them into an anonymised alternative from another country and policy context, she reconstructed the setting of a participatory meeting for our workshop in Tartu.

The show

The curtains opened, and suddenly everyone was engaged in a play. In our roles as policymakers and moderator, we followed Christina's priorly written script that determined the course of a participatory meeting: The event began with a presentation by the policymakers outlining the project's necessity, technical feasibility, and the findings of the environmental impact assessment, including proposed compensation measures. This was followed by a moderated, tightly timed Q&A session, with the moderator responsible for keeping the discussion calm and contained.

The reflection

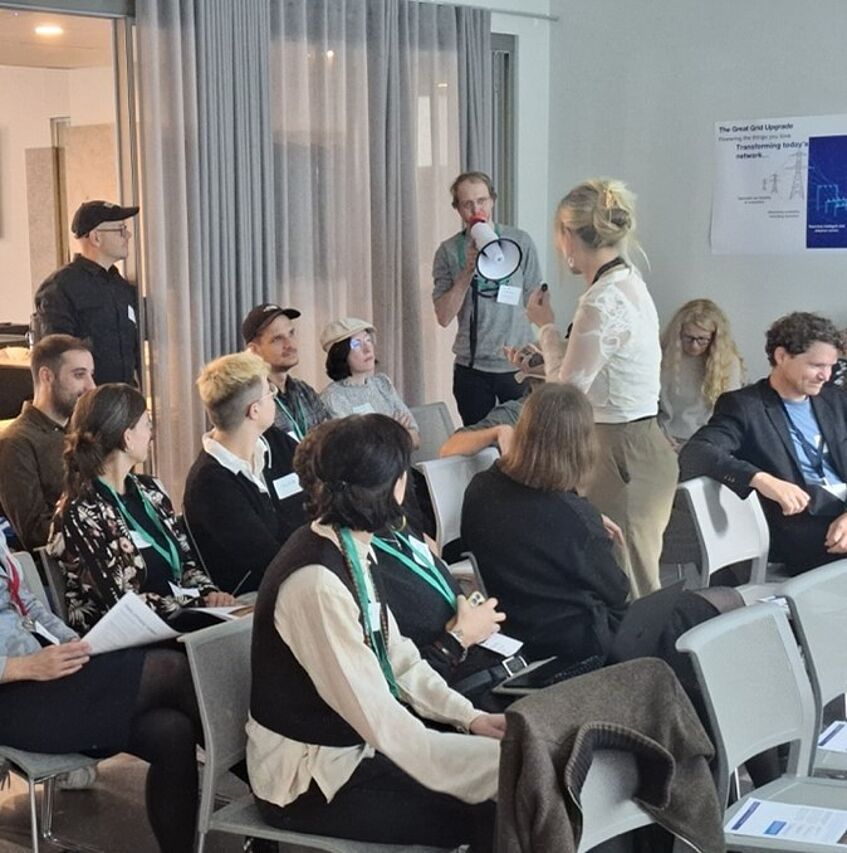

After the enactment, we together reflected on our emotional experiences. One colleague noted during the discussion: "I think I could almost feel another person's feelings." She meant that by stepping into a particular role, a person gains access to a specific emotional perspective. Another colleague mentioned: "As a citizen, I felt the particular orders I was expected to comply with" and another remarked: "I realised that I actually was mistrusting the moderator, because I asked myself: since she is hired by the municipality, is she now part of the government, or as impartial as she claims to be?" It became clear that it was not only emotions but also the setting and the tools that shaped the experience. One participant observed: "The whole space was designed for presenting; I wasn't listened to at all." Another added: "The use of the microphone, with which the moderator managed the Q&A, determined who controlled the room; the devices created differences right from the start." Christina as the moderator reflected: "When the activist pulled out his megaphone, I worried I'd lose control of the Q&A, which I was responsible for keeping calm. But by insisting on the use my microphone, explaining that the megaphone would drown out other voices, and with the policymaker making a gesture that signaled he couldn't understand anything in the noise, the activist agreed and set the megaphone down. In that moment, I suddenly realised how much authority I had."

© Tartu Ülikool

© Tartu Ülikool

Early insights on rehearsal as method: the wonderful lightness of acting

The rehearsal gave us deeper access to the actors' emotional experience. Suddenly, we could better grasp what it must feel like to participate in such an event. In interviews we can assume what a situation might have felt for the interviewee, but being engaged in an interactive play, we are somehow affected by the feelings ourselves, surrounded by others, positioned within an established order, shaped by the room's layout and tools like the microphone. We can all try to empathise with others, whether in daily life or in our work. But so many layers stand in the way: from our own prejudices, moral judgment of their character and the situation, to the simple fact of being in our body and not theirs. Somehow, when we act, something quite remarkable happens: Whether it is the abstraction invited by labelling it "theatre", or the lightness involved in playing as-if we are someone else, or the fact that we are using our whole body to understand, we are suddenly able to move beyond theorising how the other feels and for the first time being much closer to actually feeling it. It helped us not only to better understand the stakeholders we work with but even imagine what they might have needed - how the story of policy could have been told differently, and how the process and the material environment might be redesigned to build trust and strengthen relationships between citizens and policymakers.

Christina is a PhD candidate at the Urban Futures Studio at Utrecht University. Observing polarisation in multi-faceted societies facing complex challenges, she has become interested in understanding the meaning of conflict in times of political change and is keen on rethinking climate politics in more democratic ways.

Timothy Stacey is a Researcher and Lecturer at the Urban Futures Studio as well as Endowed Chair of Liberal Religion and Humanism at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht. Tim employs categories from the study of religion to understand what inspires people to engage in political processes: magic, myth, ritual, tradition.